Driving in Australia

Scenic Routes: Taking A Moment To Look Around When Driving

Recently, we flew into Sydney and had need to spend a few days to catch up with family. As we were staying in northern Sydney for a few days, we had some time between gatherings to get out and about and enjoy the sights. One of the days, we had to drive from Glenhaven up to the Hunter Valley, which is situated well north of Sydney towards Newcastle (as some of you know if you happen to live there). Wow, the Hunter Valley is a stunning place showcasing some stunning skyscapes and rolling hills around Cessnock.

Before we set off to our northern destination, we dialled up the best route with no tolls to pay on Google Maps. To our delight, we were sent on a beautiful drive through Galston Gorge. Except for a brief excursion into the Blue Mountains, up to this point we had only been travelling within Sydney itself and had little experience of any roads travelled less by the general public. This little beauty, which only kept us off the Pacific Motorway for 45 minutes or so, took us through an amazing forest with a few narrow bridges that had us skipping over steep ravines with little streams well below. Some of the turns in the road had to be taken at 5 km/h, such was the sharpness of the change in angle and the steep terrain. What a magical experience, and all of this just moments from Sydney’s urban hustle.

Another special part of the trip involved our brief look at the Blue Mountains National Park, where we travelled on the main route through Bullaburra and out to Wentworth Falls. Here we went for a decently lengthy couple of walks, one of which had us being awed by the beauty of the natural waterfalls. Some other great views of the Blue Mountains occurred as we were coming back on the homeward journey towards Sydney just as the sun was setting in all of its golden glory, carpeting the Blue Mountain forest canopy in a glowing yellow.

It got me to thinking of how easily some of those special moments are easily missed in the business of life. We could have chosen to stay in Sydney’s confines rather than take the trip south, and these adventures confirmed to me how I need to keep taking the time to enjoy the beautiful nature that’s around our home base, as well as going a little further afield when I travel somewhere new. Or maybe drive instead of fly, if time permits!

We don’t always have to travel long distances in our cars to find a magical experience in nature, where the birds are happily singing, the waterfall or river is still bubbling, and we can again discover that there isn’t that much wrong with the world after all – at least out here. Even inside our boxes of glass and steel with all the climate control, ambient lighting and connectivity, perhaps its time that we rediscovered what’s outside the bubble for a little bit. Take the scenic route, whether it’s suggested by Google Maps or not. Open the windows and smell the bush. Switch off the music and hear the crows and cockatoos squawking and screeching. If you’re the passenger, put the device down and indulge in an old-fashioned game of I Spy.

How to Transport a Bike By Car

Whether it’s the casual enthusiast, devout fitness fanatic, or professional rider, everywhere you look there appears to be a bike on our roads.

And while some cyclists have embraced the humble bike as a way to break free from being behind the wheel, the two forms of transport are not always mutually exclusive. In fact, often riders like to transport their bicycles with them on long drives.

So what’s the best way to transport your bike by car?

Use a Bike Rack

If opting to carry your bicycle on a rear mounted rack, it’s important that the rack chosen is compatible with your vehicle.

Generally one would be able to choose from straps (more suited to hatchbacks and sedans), or a tow ball mounted option (SUVs/4WDs). In the case of the latter, confirm that the load being carried is permitted by the vehicle manufacturer, and that you have access to open the boot if necessary.

Perhaps the most common option on our roads, roof racks are often used by motorists who drive station wagons or SUVs/4WDs. The rack types available vary in their transport configuration, where bicycles may be stored upright or upside down.

Regardless, the rack needs to conform to the vehicle you are driving, and should be installed in accordance with the manufacturer’s specifications. Always keep in mind that your vehicle may be restricted from safely accessing certain spaces when transporting a bike on the roof of your car.

In the Boot or Cabin

In the case of vehicles with larger internal spaces, some motorists may elect to disassemble the bike’s wheels and secure their bicycle inside the boot or rear cabin. While you might think that storing a bike inside your vehicle eliminates the risk of it causing a problem, this is far from the case.

Should you need to manoeuvre suddenly, or if you find yourself in an accident, unsecure bikes have the potential to act as a projectile, which is a major safety hazard. As such, you should ensure the vehicle is tied down with straps.

Fortunately, some hatchbacks and SUVs allow you to fold the seats down so that you can lay your bike across an expanded cargo area. This is a convenient solution that saves you time, while also making it easier to secure the bike.

If you’re driving a ute, you might just have an even simpler solution at hand! That’s right, the rear tray can serve as a very functional and capable space to take your bike with you, just about anywhere.

Other Considerations

Just to round things out, it’s worth taking the law into account. In some states like Victoria, it’s actually illegal to have a bike rack installed on your vehicle if there are no bicycles fitted.

In what is perhaps less of a surprise, it’s important to ensure your number plates are not blocked by a rear bike rack, or you’ll also be facing the prospect of dealing with an infringement notice.

Whether you are storing your bike inside your car, or transporting it via a dedicated bike rack, you may also want to consider the risk of theft. As some bikes can be worth thousands of dollars, it is not uncommon for them to be the target of crime.

Last but not least, don’t skimp on the quality of any fittings or supports you buy.

The Art of Braking

It goes without saying that there are a number of different braking technologies incorporated in the latest range of cars on the market. They might fly under the radar, if anything, but all those acronyms are more than just an abbreviation, they are a life-saving invention designed to look after you and your family’s safety.

So, what are the different types of braking technology?

The First Step: ABS

One of the early systems introduced into cars was ABS. This was something that the industry latched onto and proudly trumpeted. ABS is Anti-lock Braking System.

Before ABS arrived there were two kinds of braking styles. Most of the time it was hard on the brake pedal and look out for black smoky trails. Or there was the canny driver that would “feather” the pedal and raise and lower the braking foot to not lock up the brakes.

ABS does the same thing as the second technique, albeit faster than we could ever hope to achieve. Computer controlled sensors will have the brake pads grip and release the brake discs, slowing forward progress but not stopping the whole wheel from rotating or locking up. This increases your control over the car’s handling.

Early versions of ABS had all four wheels controlled by one or two sensors, however, it’s pretty standard now that each wheel’s brake is controlled independently.

Meanwhile, TC refers to Traction Control. A long time ago, when manual gearboxes, thirsty engines, and a heavy right foot would combine to perform a “burnout”, where the grip or traction of a tyre became less than the intended design, they’d spin and the heat would warm the rubber to a point where the tyre would begin to smoke.

Traction Control stops this from happening. Whether it’s intentional, or in the case of either climbing a wet bitumen road, or turning a sharp corner at slow speed then accelerating, a computer sensor steps in and reduces power momentarily to reduce the lack of traction.

New Braking Technology

Today, a wide range of advanced technologies are designed to improve braking efficiency and enhance overall vehicle safety. One of these features includes ESP/VSC (Electronic Stability Program or Vehicle Stability Control). It is also referred to as DSC (Dynamic Stability Control) or ESC (Electronic Stability Control).

In essence, each of these systems do the same thing. They combine with Traction Control and rely on electronic sensors to measure wheel rotation speed, the direction of travel of the vehicle, the angle of the vehicle, and if a pre-programmed point of no return might be reached. At this point, the stability program will apply brakes to the wheel, or wheels it deems require assistance.

This can be done without the driver’s knowledge. For example, on a wet and slippery road, the system may quietly work in the background by gently applying braking force. In effect, the system helps the car stay on a straighter, tighter, driving line.

EBD, or Electronic Brake Distribution, is a form of brake technology that automatically varies the amount of force applied to each of a vehicle’s wheels, based on road conditions, speed, and loading. It works hand-in-hand with ABS.

Finally, there’s Brake Assist, which provides extra braking pressure if the car’s onboard computers think that it is required. In today’s cars, this tends to be partnered with a forward-looking sensor setup and cruise control.

New South Wales and New Zealand: Spot The Difference

Thinking of heading across the ditch to New Zealand this winter for a spot of skiing or sightseeing, picking up a rental car so you can travel according to your own fancies? If you’re heading over from New South Wales, you’ll find that although a lot of things are the same when driving in New Zealand compared with back home, there are quite a few sneaky little differences that might trip you up. Most of the road rules and road signs will be familiar, but some aren’t and some are nonexistent. Here’s a handful of some differences you might notice:

Even in the middle of what passes for a city, there’s way less congestion. In the busiest parts of town during rush hour, you’ll get some congestion, but nothing like you’ll find in the middle of Sydney.

People don’t honk the horns half as much. OK, someone might honk if the driver at the front of the queue is naughtily on their phone or daydreaming and doesn’t notice that the light has turned green, but drivers seem more patient in, say, Christchurch than they are in Sydney and will jump on the horn a lot slower.

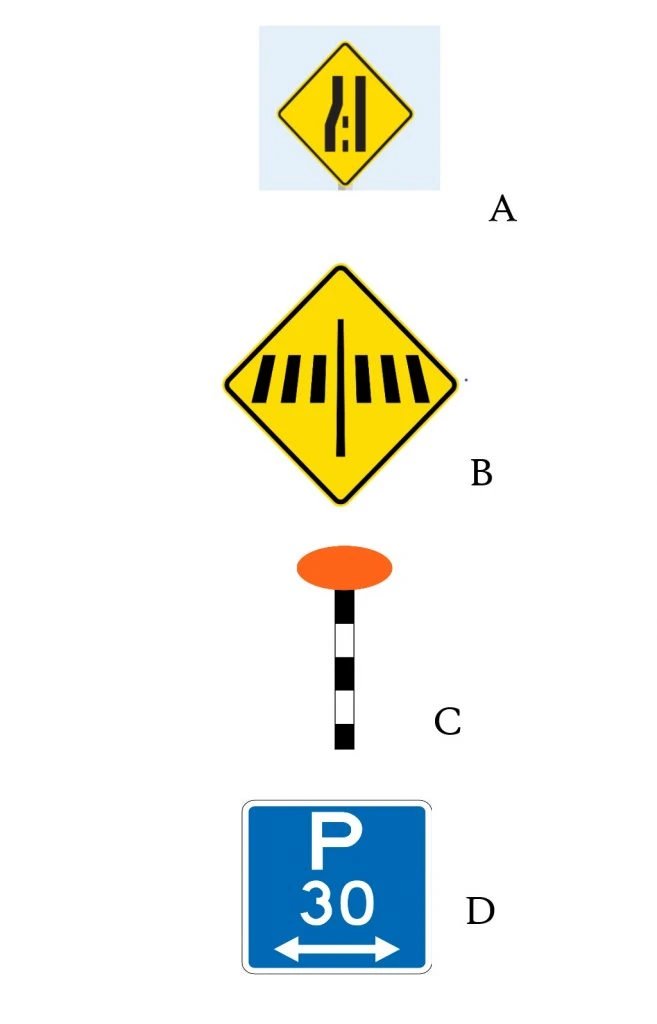

You don’t get handy “merge ahead” signs. Instead, you get Sign A in the diagram below. The idea is to “merge like a zip”, left-right-left-right, etc.

Pedestrian crossing (zebra crossing) signage is different. The familiar sign with the pair of walking legs isn’t on the zebra crossing itself, and you don’t get the zigzag road markings leading up to the crossing. Instead, you get the warning sign (Sign B), with an orange dot on a stripy pole on the crossing (Sign C).

Pedestrian refuge islands aren’t signed. This means that at any time a centre island divides two lanes of traffic, there could be a lurking pedestrian hoping to cross. Keep your eyes open (and the pedestrian will be doing the same). Refuge islands with designated cut-downs for pedestrians are common near roundabouts.

Parking limits are in minutes, not hours. If you got all excited about a sign saying “P5” or “P15”, believing that you’d be able to park there for 5 or 15 hours, I’m sorry to disappoint you. You’ve only got 5 or 15 minutes. If you’re lucky, you can find signs giving you 90, 120, 180 or 240 minutes of parking (if you look hard enough), meaning 1½ hours, 2 hours, 3 hours and 4 hours, respectively. Sign D is a typical example.

If you’re in an urban area, the speed limit is probably 50 km/h. There aren’t as many 60 km/h sections. Local traffic areas don’t exist, so assume that it’s 50 km/h unless told otherwise.

Even on the motorway, you won’t get to go 110 km/h legally. At the time of writing, the Kiwi Powers That Be are discussing the introduction of 110 km/h sections on some main motorways. However, this is still in the discussion stage, so if you head over this winter, you’ll have to keep your speed to a maximum of 100 km/h when in rural areas.

School zones don’t have the times handily displayed. If the signs are flashing, the reduced speed limit (either 30 or 40 km/h) applies; if they’re not flashing, the usual speed limit (usually 50 km/h) applies.

Speed cameras are sneaky. Permanent ones – and there are some – don’t have warning signage. There have been calls from lobby groups to introduce signs warning you that there are permanent speed cameras in position, but there aren’t any yet. You may, however, see some signs warning you about red light cameras. NZTA has taken to calling both speed cameras and red light cameras by the twee name of “safety cameras” but the majority of Kiwi think this is a cringeworthy attempt to not call a spade a ruddy spade. The NZTA Journey Planner website has a map showing you where the mobile ones are, so check this when you plan your journey (it’s a good idea to check it even if your right foot isn’t on the heavy side, as it will also tell you if roads have been closed or if there are major roadworks underway).

Witches’ hats everywhere. The roading contractors just LOVE witches’ hats and will put up heaps of them even weeks before the actual road works take place, and these will probably be the last thing they take away. They’ll also start appearing up to 1 km ahead of the road works (in rural areas). They’ll also put up insane numbers of the things. I have no idea what they’re thinking. Do they think that if there’s a car-sized gap in the middle of a long row of witches’ hats that I’m going to decide to cross the line? Incidentally, not many Kiwis will use the word “witches’ hat” but will call them a “road cone”. Near universities, you may spot some in unusual places, such as up trees.