Fueling your Car

Tesla Hikes Charging Rates at its Supercharger Stations

While it’s meant to be a frontrunner for the rush to electric vehicle adoption, Tesla has made a decision that has raised the eyebrows of industry onlookers, increasing the cost of its charging rates at Supercharger sites.

The move is understood to have been implemented silently over the last few weeks, despite the absence of any official confirmation from the auto-maker. The increase in price is equivalent to a near 25% jump, with the charge per kW increasing from $0.42 per kW to $0.52 per kW.

How will owners be impacted?

Australian Tesla owners have had little say in the matter, with no heads up given before the price increase. Of course, it would likely be out of owners hands even if they were advised, since the company’s 35 Supercharger sites across the nation have been an integral part of the broader infrastructure network being rolled out to support electric vehicle uptake. That network is set to expand by a further 7 soon enough, with additional sites currently being built.

To better understand the cost impact, one estimate provided by Caradvice focused on the Model 3 Long Range. Their estimates suggested that charging the Model 3 Long Range from an empty battery to a full battery would now cost approximately $43.30, a notable increase from the former price of around $35. That might still be some part cheaper than most if not all ICE vehicles, however, let’s not forget that some technology companies – which Tesla certainly is as much as an auto-maker – are price makers.

We certainly hope the manufacturer doesn’t plan to push through any further price hikes in the near-term, because we might start to see questions being asked as to the value motorists are getting. It’s one thing for the latest electric vehicles to be equipped with long range capacity, however, having to paying more for the ‘luxury’ to charge them at Tesla’s sites may be a contentious move, even if the car company has recently taken an axe to the retail price of its cars.

Nonetheless, as far as driver uptake goes, shifting numbers around to pay less up-front and then pay more while in use could gain traction – provided motorists are actually aware of what they’re signing up for. That’s the missing thing here, however, greater transparency. And Tesla will need to remember they might enjoy an early-mover advantage right now, but will it last if you alienate your customers through non-communicated price hikes?

BMW Updates And Hyundai Hydrogen Power.

BMW continue to roll out new or updated models at an astonishing rate in 2020. For the brand’s M Pure range, there will be another two models being added. Dubbed M135i xDrive Pure and M235i xDrive Pure, they’ll come with an extensive range of standard equipment and sharp pricing. The M135i xDrive Pure is priced at $63,990 and the M235i xDrive Pure at $67,990. This is a $5K savings in comparison to related models.

Power for both comes from BMW’s TwinPower Turbo four. 225kW and 450Nm spin an eight speed auto Sport Steptronic transmission that send grip to all four paws via the xDrive system with an LSD on the front axle. Steering column paddle shifts are standard. External style cues comes from the sharing of styling packages, wheels, and tyres.

BMW lists the M135i xDrive Pure with M Sport steering, 19 inch alloys in M spec Cerium Grey that wrap M Sport Brakes and blue calipers. Inside there is a BMW specification Head Up Display and the bespoke Driving Assistant package. There is Lane Departure Warning, Lane Change Warning, Approach Control Warning with city-braking intervention, Rear Cross Traffic Warning, Rear Collision Prevention and Speed Limit Info.  There is also their Comfort Access System that features Electric Seat Adjustment, driver’s side seat memory function with the seats in Trigon black and Alcantara, and dual zone climate control. On top of that is the M135i xDrive which adds a panoramic glass roof, adaptive LED front lights and “Dakota leather upholstery, plus a thumping Harman Kardo audio system. The value here is over $6K. The same packages apply to the M235i xDrive Pure and M235i xDrive.

There is also their Comfort Access System that features Electric Seat Adjustment, driver’s side seat memory function with the seats in Trigon black and Alcantara, and dual zone climate control. On top of that is the M135i xDrive which adds a panoramic glass roof, adaptive LED front lights and “Dakota leather upholstery, plus a thumping Harman Kardo audio system. The value here is over $6K. The same packages apply to the M235i xDrive Pure and M235i xDrive.

The stable now consists of M135i xDrive Pure and M235i xDrive Pure, the M340i xDrive Pure M550i xDrive Pure, before migrating to X2 M35i Pure, X5 M50i Pure, and X6 M50i Pure.

The two new additions will be available in the coming months.

Hydrogen is being touted by Hyundai as the next thing in vehicle power sources and the Korean company has moved swiftyly into areas outside of passenger vehicles. In a global first, Hyundai have sent to Switzerland 10 units of their hydrogen powered machine called XCIENT. This commences a roll-out which will comprise 50 units to start with. A goal of 1,600 trucks are expected to be released by 2025. Due to the tax structures in Switzerland, Hyundai chose the country with one levy, the LSVA road tax on commercial vehicles which does not apply for zero-emission trucks, as a main consideration. That nearly equalises the hauling costs per kilometre of the fuel cell truck compared to a regular diesel truck. And thanks to the green energy costs from hydropower, it counts towards the eco performance of the country. The power system has a pair of 95kW hydrogen fuel cells. Just on 32 kilos of the fluid form are stored across seven super-strong storage tanks. Hyundai specifically developed the system for the truck with the current and expected infrastructure in Switzerland, and have engineered in a range of 400 kilometres. Refuel time minimises downtime with anywhere from 8 to 20 minutes. Hyundai says that this should work in with obtaining “the optimal balance between the specific requirements” of the customer base and that refuel infrastructure. In Cheol Lee, Executive Vice President and Head of Commercial Vehicle Division at Hyundai Motor, opines: “XCIENT Fuel Cell is a present-day reality, not as a mere future drawing board project. By putting this groundbreaking vehicle on the road now, Hyundai marks a significant milestone in the history of commercial vehicles and the development of hydrogen society.”

The power system has a pair of 95kW hydrogen fuel cells. Just on 32 kilos of the fluid form are stored across seven super-strong storage tanks. Hyundai specifically developed the system for the truck with the current and expected infrastructure in Switzerland, and have engineered in a range of 400 kilometres. Refuel time minimises downtime with anywhere from 8 to 20 minutes. Hyundai says that this should work in with obtaining “the optimal balance between the specific requirements” of the customer base and that refuel infrastructure. In Cheol Lee, Executive Vice President and Head of Commercial Vehicle Division at Hyundai Motor, opines: “XCIENT Fuel Cell is a present-day reality, not as a mere future drawing board project. By putting this groundbreaking vehicle on the road now, Hyundai marks a significant milestone in the history of commercial vehicles and the development of hydrogen society.”

A key attraction of the hydrogen technology is how well, like diesel, that hydrogen is admirably suited to long distance driving and the quick turn-around times required in heavy haulage. Engineering can also build engines, such as they have here, to deal with expected terrain such as the road system in a mountainous country. To that end, Hyundai is developing a unit for a tractor with a mooted range of 1,000 kilometres with markets such as the United States and Europe in mind.

The origination of the program goes back to 2019 with a joint venture named Hyundai Hydrogen Mobility, a partnership between H2 Energy in Switzerland and Hyundai. The basis for the trucks being operated will work around a lease agreement with commercial operators and on a pay-per-use agreement. This helps budget requirements as there is no immediate up-front costs.

Depending on the results, with expected high success levels, the program may be expanded to other European countries.

What Did People Use Petroleum For Before The Internal Combustion Engine?

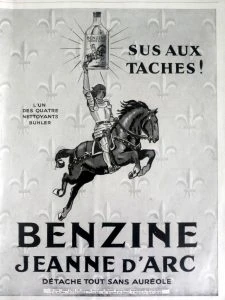

Vintage advertisement for benzine-based stain remover.

Petroleum is currently the backbone of the motoring industry, despite the push for alternate fuel sources such as biodiesel, electricity, ethanol, etc. Ever since Karl Benz first invented the internal combustion engine and fitted it to the horseless carriage, vehicles have run on petroleum of some type – apart from a brief period where Diesel engines ran on vegetable oil.

On Bertha Benz’s legendary first long-distance drive in her husband’s new invention, she ran out of fuel and had to stop and pick up more from the nearest pharmacy. It’s easy to just take in that sentence and think what a funny place a pharmacy is to pick up petrol until you stop and think about it: why was a chemist’s shop selling petrol? What on earth were people using it for before we had cars to put it in?

Petroleum has certainly been known for at least four millennia. The name comes from Ancient Greek: petra elaion, meaning “rock oil”, which distinguished it from other sorts of oil such as olive oil, sunflower seed oil and the like. The stuff was coming out of the ground all around the world, and quite a few ancient societies found a use for it.

The most useful form of petroleum back in the days BC (as in Before Cars as well as Before Christ) was bitumen, the sticky variety that we now use for making asphalt for road surfacing. Bitumen (also called pitch or tar) didn’t just stick to things; it was also waterproof. As it was a nice waterproof adhesive, it came in handy for all sorts of things, from sticking barbed heads onto harpoons through to use as mortar – the famously tough walls of the ancient city of Babylon (modern-day Iraq, 2which is still oil-rich) used bitumen as mortar. The Egyptians sometimes used it in the process of mummification, using it as a waterproofing agent. In fact, the word “mummy” is thought to derive from the Persian word for bitumen or petroleum, making mummies the very first petrolheads.

For the next thousand years, petroleum in the form of bitumen was mostly used for waterproofing ships, to the extent that sailors became known as “tars” because they tended to get covered with the stuff. In the 1800s, it was used to make road surface – before there were cars to run on them.

It was probably the Chinese who first had the idea of using petroleum as fuel. “Burning water” was used in the form of natural gas for lighting and heating in homes, and in about 340 AD, they had a rather sophisticated oil well drilling and piping system in place.

The bright idea of refining bitumen to something less sticky and messy first occurred in the Middle East (why are we not surprised?) at some point during the Middle Ages. A Persian alchemist and doctor called Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi (aka Rhazes) wrote a description of how to distil rock oil using the same equipment the alchemists used for distilling essential oils. The end result was what we know today as kerosene, and it was a lot more flammable. Kerosene was used for lamps and in heaters, especially as it was a lot cleaner than coal. It was also used in military applications. Naphtha (one of the other early names for petroleum products) was possibly one of the mystery ingredients in Greek fire.

Kerosene and the like really took off during the Age of Coal and the Industrial Revolution, as they were by-products of the coke-refining industry. About this time, scientists started tinkering around with various ways to refine crude oil into products like paraffin and benzene and benzine. Benzene and benzine are not named after Karl and Bertha Benz the way that diesel fuel is named after Rudolf Diesel. These words are actually derived from “benzoin” and benzene was given its official name by yet another German scientist in the early 1800s. The similarity between the surname Benz and the name of the petrol product is pure coincidence – really!

Kerosene and the like really took off during the Age of Coal and the Industrial Revolution, as they were by-products of the coke-refining industry. About this time, scientists started tinkering around with various ways to refine crude oil into products like paraffin and benzene and benzine. Benzene and benzine are not named after Karl and Bertha Benz the way that diesel fuel is named after Rudolf Diesel. These words are actually derived from “benzoin” and benzene was given its official name by yet another German scientist in the early 1800s. The similarity between the surname Benz and the name of the petrol product is pure coincidence – really!

The petrol product (ligroin) that Bertha Benz picked up at the pharmacy was probably sold as a solvent, like the ad in the picture up the top. This was one of the most common household uses of bottled refined petroleum. Petrol is still very good as a solvent and can bust grease like few other things, so it was popular as a stain remover and a laundry product. It might have ponged a bit and you had to be careful with matches, but it was nice and handy, and meant you could get that candle-grease off your suit without putting the whole thing through the wash. Other uses for benzene that sound downright bizarre to us today included getting the caffeine out of coffee to make decaf and aftershave. REALLY don’t try this one at home, even if you love the smell of petrol, as we now know that petrol products are carcinogenic and you should keep them well away from your skin, etc.

It was the widespread use of petroleum-based products such as paraffin in the 1800s that made the demand for whale oil drop dramatically. This happened just in time to stop whales being hunted to extinction. Using petrol was the green thing to do and helped to Save The Whales. Now that whales have been saved and are thriving, cutting down on the use of fossil fuels is the main focus of a lot of environmental groups. Irony just doesn’t seem to cover it.

The Story Of Diesel

It’s something we hear about our think about just about every day, whether we drive a diesel-powered vehicle or a petrol-powered one. There you are, pulling up at the local bowser and you have to stop and do a quick check to make sure that you get the right one, diesel rather than petrol or vice versa. You probably don’t stop to think about the word diesel much or the history behind it.

It’s something we hear about our think about just about every day, whether we drive a diesel-powered vehicle or a petrol-powered one. There you are, pulling up at the local bowser and you have to stop and do a quick check to make sure that you get the right one, diesel rather than petrol or vice versa. You probably don’t stop to think about the word diesel much or the history behind it.

Most of us think that diesel engines are called diesel engines because they run on diesel. After all, a petrol engine runs on petrol (which, for you word boffins out there, is short for petroleum, which is derived from the Latin petra oleum, translated “rock oil”). However, this isn’t the case. We call the fuel diesel because it was what went in a diesel engine, i.e. the sort of internal combustion engine invented by Herr Rudolf Diesel back in 1893. If you want to be picky, what we use is “diesel fuel” which we put into a diesel.

The story of the diesel engine starts back in the days of steam. Steam power, though a major breakthrough that transformed the world and took us into the era of machines rather than relying on muscle power, was pretty inefficient. You needed a lot of solid fuel to burn and you needed water that could be boiled to produce the steam, and you needed to build up a good head of steam to get the pressure needed to drive the locomotives, paddle steamers and machines. Steam was really inefficient – up to 90% of the potential energy was wasted – and it was pretty bulky (think about steam trains, which need a caboose or a built-in tender to carry the fuel and water). The hunt was on for something that could provide the same type of oomph and grunt but with less waste (and possibly less space).

In the 1890s, a young engineer named Rudolf Diesel came into the scene and started work on developing a more efficient engine. One of his earlier experiments involving a machine that used ammonia vapour caused a major explosion that nearly killed him and put him in hospital for several months. Nevertheless, in spite of the risks, Diesel carried on, and began investigating how best to use the Carnot Cycle. His interest was also sparked by the development of the internal combustion engine and the use of petroleum by fellow-German Karl Benz.

The Carnot Cycle is based on the First and Second Laws of Thermodynamics, which more or less state that heat is work and work is heat, and that heat won’t pass of its own accord from a cold object to a hotter object. This video gives a very catchy explanation of these laws:

The Carnot Cycle is a theoretical concept that involves heat energy coming from a furnace in one chamber to the working chamber, where the heat turns into work because heat causes gases and liquids to expand (it also causes solids to expand but not so dramatically). The remaining heat energy is soaked up by a cooling chamber. The principle is also used in refrigerators to get the cooling effect.

Diesel’s engine was based on the work of a few other inventors before him, as is the case with a lot of handy inventions. Diesel’s engine was the one that became most widespread and proved most popular, which is why we aren’t putting Niepce, Brayton, Stuart or Barton in our cars and trucks. In fact, we came very close to putting Stuart in our engines, as Herbert Ackroyd Stuart patented a compression ignition engine using similar principles a couple of years before Rudolph Diesel did.

The general principle of a Diesel engine is that it uses compressed hot air (air gets hotter when it’s compressed, which is why a bicycle pump feels hot when you’ve been using it for a while) to get the fuel in the internal combustion engine going. This is in contrast to a petrol engine (which we really ought to call an Otto engine, as it operates on the Otto Cycle rather than the Diesel Cycle), which used sparks of electricity to get the fuel and air mix going. Petrol engines compress the air-fuel mix a little bit – down to about 10% of its original size, but a diesel engine, the air is compressed a lot more tightly. More details of how it works would probably be better described in a post of its own, so we’ll save the complicated explanation for later.

Diesel fuel doesn’t need to be as refined as what goes into petrol engines, which is what makes diesel engines a bit more efficient than their equivalents that run on more refined petrol (makes you wonder why “petrolheads” are considered to be coarse and crude). The fuel is more energy-dense and it burns more completely – and it needs less lubrication, which means less friction, which is also more efficient.

Herr Diesel’s original idea was to have his engine run on something that wasn’t this fancy petroleum stuff, which was mostly used medicinally to treat headlice at that stage. The first prototype used petrol as we know it. Later models used the cheap fraction that now bears his name. Even later refinements ran on vegetable oil, with the grand idea that people could grow a source of fuel rather than mine or drill for it. One of the great mysteries of the story of diesel is why they switched to fossil fuels when the peanut oil that Diesel raved about worked so well. Now we’re all excited about biofuels and especially biodiesel once again… Was there some conspiracy at work?

However, how diesel engines came to run on fossil fuels rather than plant oil is not the only mystery about Rudolf Diesel. His death was also unexpected and mysterious. In late 1913, this German inventor was on his way by ship to the UK for a conference. One night, he headed off to his cabin and asked the stewards to wake him early in the morning. However, he vanished during the night, leaving his coat neatly folded beneath a railing. Ten days later, his body, recognisable only from the items in his pockets, was pulled from the sea.

How his body came to be found floating in the English Channel is a mystery. Perhaps the problems with his eyesight left over from his accident with the ammonia vapour explosion and a rough sea led to an accident. Perhaps he committed suicide, as a lot of the fortune his invention had earned him had gone into shares that devalued. Or perhaps foul play was at work. After all, in 1913, tensions were building between Diesel’s native Germany and the UK, where Diesel had planned to meet with engineers and designers for the Royal Navy. This was the era of the Anglo-German Naval Race, where the German and British navies were in an all-out arms race to get control of the economically important North Sea. When Diesel was making his ill-fated crossing, the Germans had the use of the more efficient diesel technology but the British had the formidable Dreadnought class of steam-powered battleships. The arms race was officially over, as Germany had agreed to tone things down in order to placate the British – who had alliances with the two other political powers that were at loggerheads with Germany. It’s perfectly possible that in spite of this and because of the political tension of the time, the idea of the firepower of the Dreadnought combined with the efficiency of the diesel engine was just too much for Kaiser Bill’s government…